What is urbex?

In 1861 the poet Walt Whitman described in verse his forays into the abandoned Atlantic Avenue tunnel in the Brooklyn borough. An illustrious forerunner for urban exploration (abbreviated to urbex or UE), a phenomenon expanding across the globe, involving thousands of people of both sexes and individuals of all ages.

Who is the urbexer?

The urbexer explores ‘shady areas‘ with the utmost respect, without invasion or tampering. He/She is a ‘guest’ and explorer of structures forged by the hand of man, often abandoned, in ruins, forgotten, desolate or made off-limits. The places he visits are numerous and of different types: disused industrial sites, uninhabitable hospitals or asylums, abandoned military installations, fallen factories, forgotten castles and monuments, uninhabited cottages, sewers and drains, villas and basements. He/She moves around in groups or individually, what is ‘hidden‘ and ‘invisible‘ to the sight of any passer-by is for him/her a new treasure to discover, a new adventure to catapult him/herself into, a new danger to confront.

Why abandoned places?

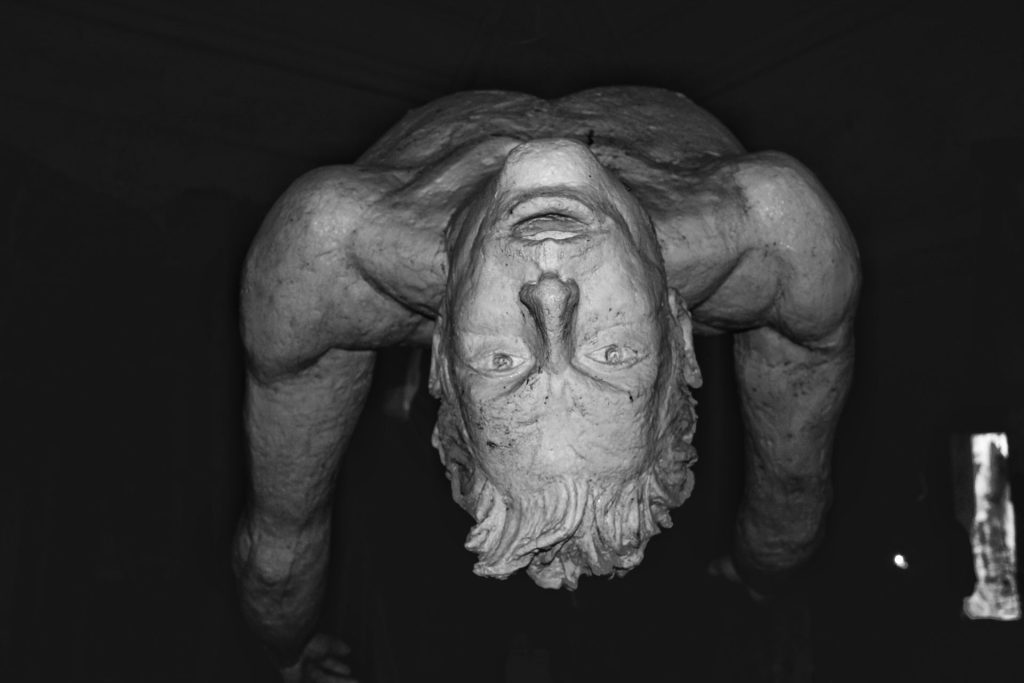

Abandoned buildings thus acquire a different ‘purpose’ from that for which they were originally designed. In abandonment, nature becomes poignant again: ivy slowly wraps the walls and rust paints the steel doors in multicoloured patinas. It is this ‘grey’ zone, this structural fragility capable of breaking down the built order, between civilisation and nature, that the explorer finds particularly attractive. Time, the material co-artist of it all, shapes the subject and makes it appreciable to the urbexer’s taste. His spaces, relatively free from performative and aesthetic regulation, are sites where the city disappears, reappearing in another form. An urban area that is reinterpreted through the juxtaposition and overlapping of memories, corridors, walls, dust, beams and bodies.

The abandoned space is uncertain, fluid, and full of different forces, obstacles, energies and currents. The explorer moves in different directions and in addition to leaping from the present to the past and back again, he/she may become trapped in a limbo, a space-time capsule. The urbexer tests him/herself by abandoning, crossing and cleaving through the ambiguity of these boundaries. The power of the forbidden and of abandonment triggers intimate disturbances and emotions.

As Marc Augè would say, abandoned places within the phenomenon of urban exploration are identitary, bearers of memory, social relations, history and belonging. Places capable of awakening deep emotions and lost histories, fertile ground for desires and fears intertwined with the explorer’s experience.

History of urban exploration (urbex)

People have been venturing into abandoned places for a long time, yet the term ‘urban exploration’ was first coined in a 1996 edition of ‘Infiltration’ magazine.

Besides Whitman, urbexers include other well-known personalities. The Parisian Dadaists, for example, in 1920 organised tours through deserted churches and other sites ‘that had no reason to exist’. MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) students, upon returning to the United States in the late 1950s, led tours of tunnels and rooftops around their campus, calling their practice ‘hacking‘, a term that decades later was adopted by the ‘technical’ talk of urbex.

Over the past two decades, particularly since the mid-2000s, an emerging global subculture has coalesced around urban exploration. Hundreds of thousands of blogs and online discussion forums have been facilitated by the advent of the internet. Blogs such as urbexplayground, Urbexnl, Urbex-travel collect countless abandoned places and urban explorations around the globe and document their history through articles and images. The culture of the EU forges its own identity from which emerges a community subject to precise rules. A small but growing research literature has accompanied the proliferation of the practice. One need only read Bennett’s 2011 essays to those of Garrett, 2013 or Mott and Roberts.

Heroic life, Edgeworker and urban exploration

But the practice of urbex besides the excitement can also offer some problems. As James Nastor tells us in his 2007 article ‘The art of urban exploration‘, rotten wood, chemical residues, rusty, razor-sharp nails and unstable ground are constant threats at most abandoned sites. It is the responsibility of the explorer to avoid death or injury in these areas.

When asked: ‘What reason brought you to visit Chernobyl‘, the two Kyiv urbexers Vladimir and Artyom, frequenters of Chernobyl, replied: ‘Such an opportunity so close to me, I wanted to try the extreme. The abandoned places in Kyiv did not interest me, I was interested in something bigger and more distant.

Artyom adds “The motivation is obvious, who wouldn’t want to see what the Earth might look like when the human race becomes extinct? “.

These explorations are trials to be overcome in order to fulfil what sociologist Mike Featherstone calls the ‘heroic life‘, made up of adventure, courage, thrill, and adrenalin that is confronted with the risk of death. The transgression and violation of certain norms is a source of vitality.

To indicate the place where norms are negotiated and boundaries contested, the risk of dangerous experiences that some groups intentionally seek with the pleasure that follows, Stephen Lyng uses the term edgework, ‘extreme experiments‘, already used by Hunter S. Thompson. This combination of intense emotional excitement and focused attention leads edgeworkers to experience alterations in the perception of time and space, feelings of ‘hyperreality‘ with a sense of the experience as deeply authentic and alive. Edgework represents both a challenge to limits, daily routines and social expectations and a greater sense of control over fear. In essence, urbexers navigate the edge where conformity, safety and thrill find a point of balance. Deborah Lupton, echoing Stephen Lying, conceives of edgework as emotional tests that settle into clearly delineated boundaries ‘the boundary between life and death, between consciousness and the unconscious, between sanity and insanity, between the experience of an ordered self and environment and the experience of an upside-down self and environment’.