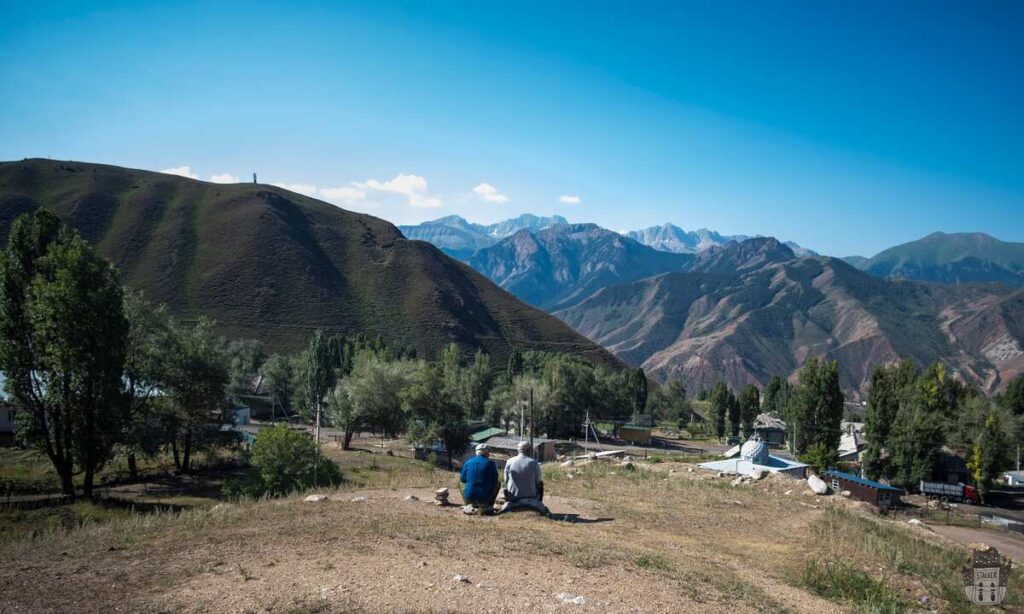

The journey to Ming-Kush, in the Jumgal district of the Chirghisa region of Naryn, was like a plunge into the past. Ming-Kush, ‘Thousand Birds‘ in English, was officially founded in 1955 around some uranium mines. During its heyday, the population reached 20,000, which dropped to 2,000 after the dissolution of the Soviet Union and the subsequent closure of the factories.

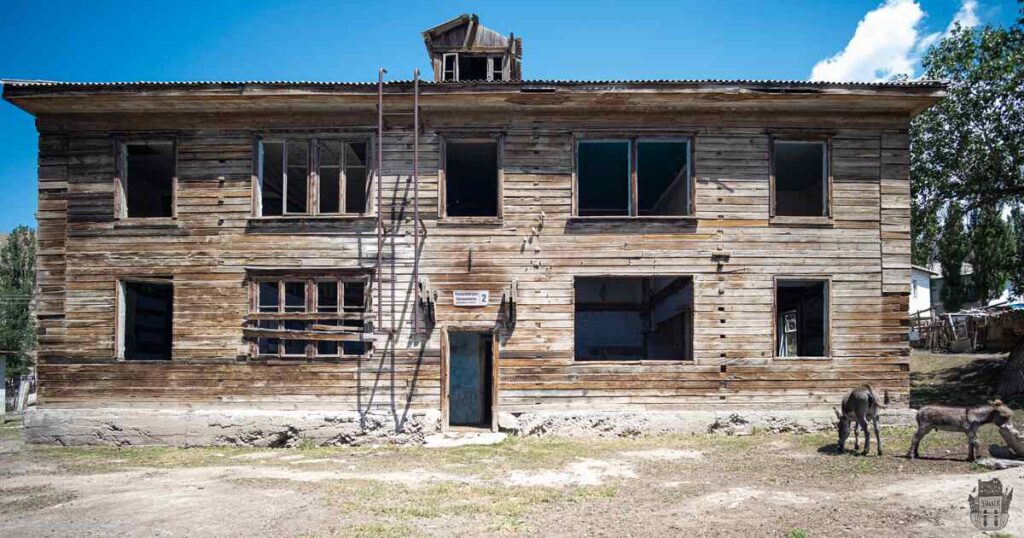

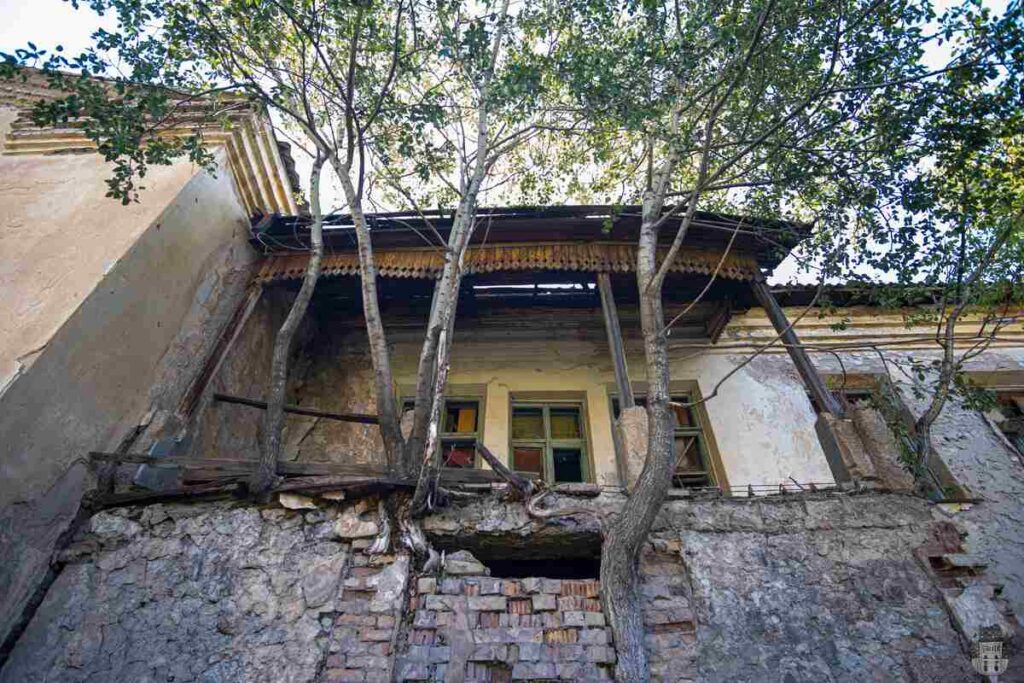

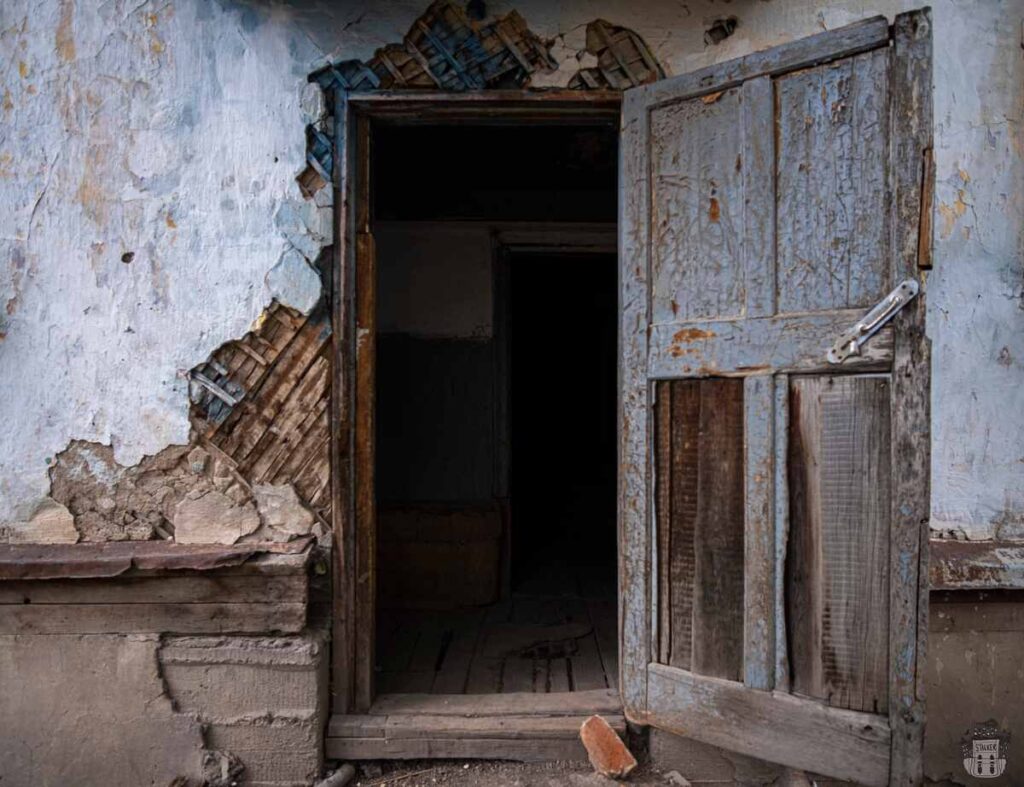

Today, there are numerous abandoned and uninhabitable buildings in the declining village. Radiation levels in the area can be up to 10 times higher than normal and most of the residents are out of work and their lives depend on the meagre pensions they receive.

The Dawn of the Atomic Age

Uranium mining in the USSR began in 1942, with the first mine established in Taboshar, Tajikistan. Forced labour, mainly prisoners from the Gulag, was used to extract and process the material. The uranium rush accelerated after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. We talk about this with Dastan, a Kyrgyz guide, who tells us how during the Cold War Ming-Kush was classified as a ‘closed city‘, i.e. an urban settlement where strict travel and residency restrictions applied, requiring special permission for visits or overnight stays. These are places with sensitive military facilities or secret research sites that provide far more space and operational autonomy than any military base.

The Glory Days of Ming-Kush

“Between 1946 and 1951, more than 600 German soldiers assisted by prisoners working twelve hours a day were operating to build Ming-Kush,” Dastan continues. During this period, the uranium mined at Ming-Kush played a key role in the construction of the USSR’s first atomic bomb and the Vostok 1 spacecraft to launch the first man into space.

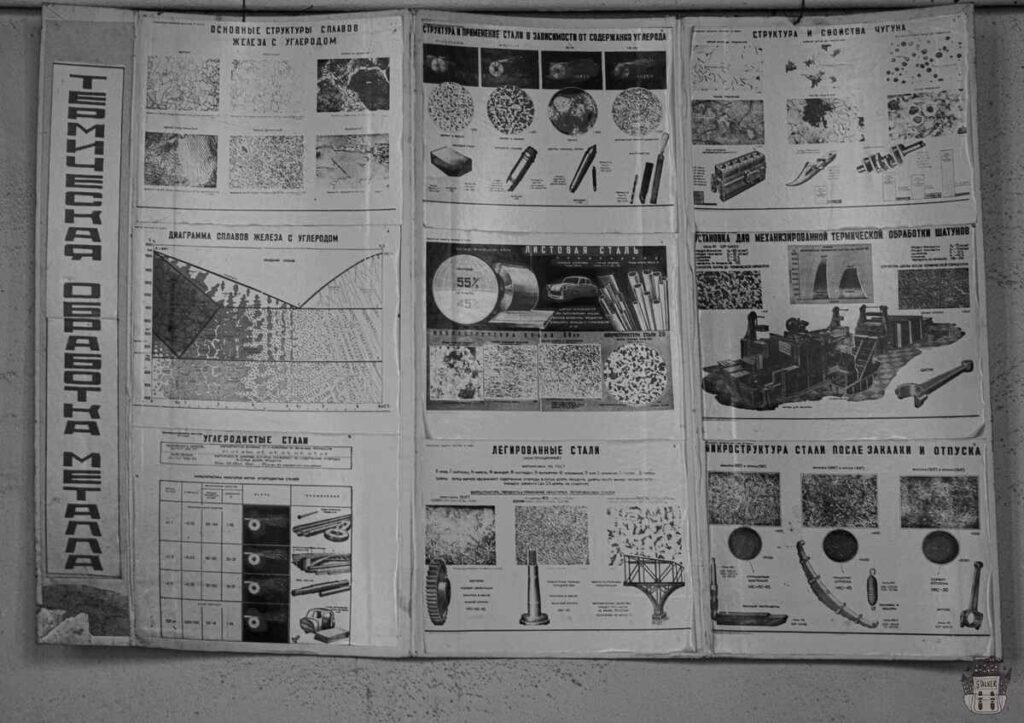

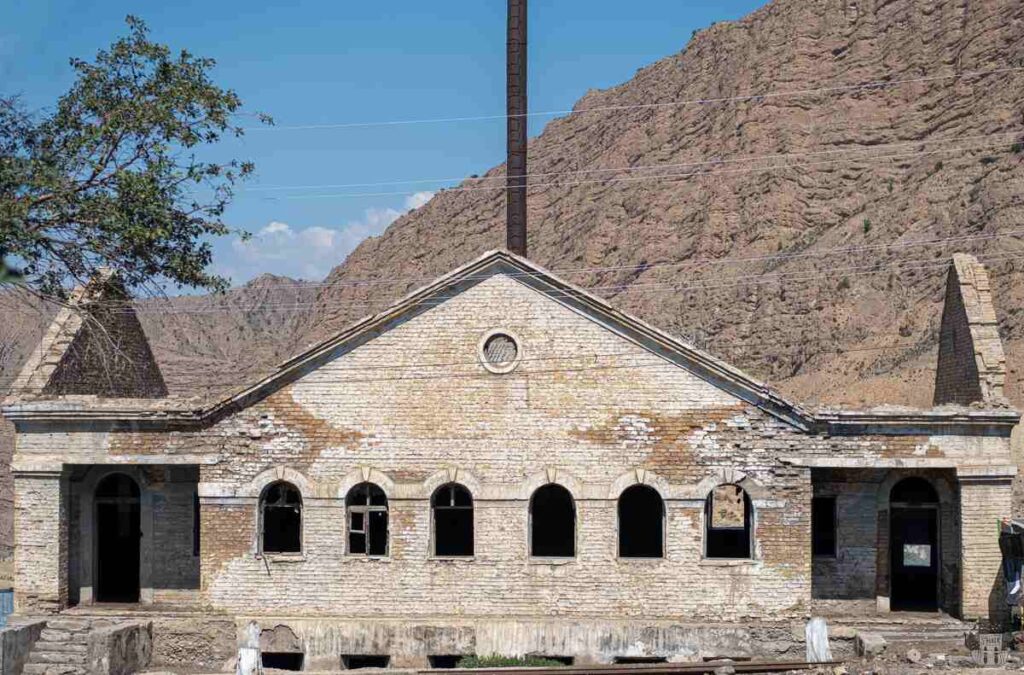

“In 1979, the mines in Ming-Kush were closed and concentrated in certain areas of Kazakhstan where more advanced technologies were used,’ Dastan continues. ‘To ensure that the population would not be left unemployed, the authorities built new industrial plants, such as pen and marker factories.

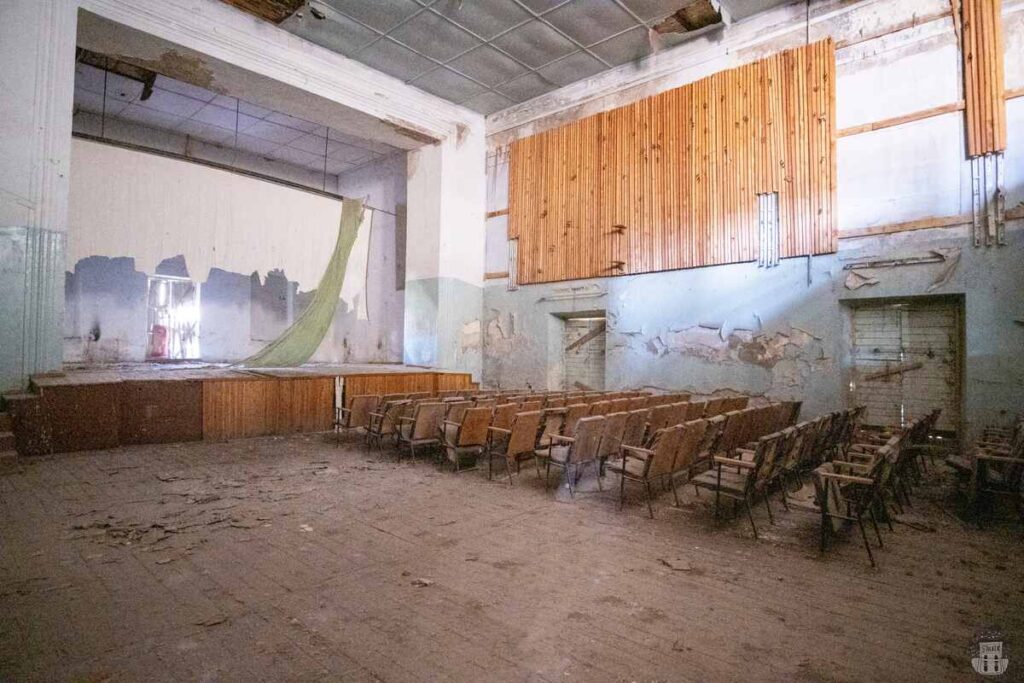

Residents recall the heyday of Ming-Kush with nostalgia. One former worker recounts ‘When the Soviets were here, there was a lot of work! More than 20,000 people in Ming Kush! I worked in the factory and everyone had enough money’. The village boasted numerous infrastructures including polyclinics, hospitals, police, fire brigades, schools, shops, cafes, canteens, cinemas, and residents had access to products and services usually reserved for big cities.

The Fall of an Empire and Ming-Kush

However, there were the risks of uranium mining and processing, known to the miners themselves. Today, the inhabitants do not want to answer when it comes to illness and cancer. One lady is aware of this and does not talk about it, merely stating: ‘My father was a miner and my mother worked at the combine harvester. They both enjoyed good health and were blessed with nine healthy children. My father lived to the impressive age of 90’.

With the dissolution of the Soviet Union, the town of Ming-Kush suffered a dramatic decline. The once-booming industrial hub has seen an impressive decline in population, and the closure of factories has further exacerbated the economic crisis, leaving many jobless with unemployment now touching 70%.

A day in Ming-Kush

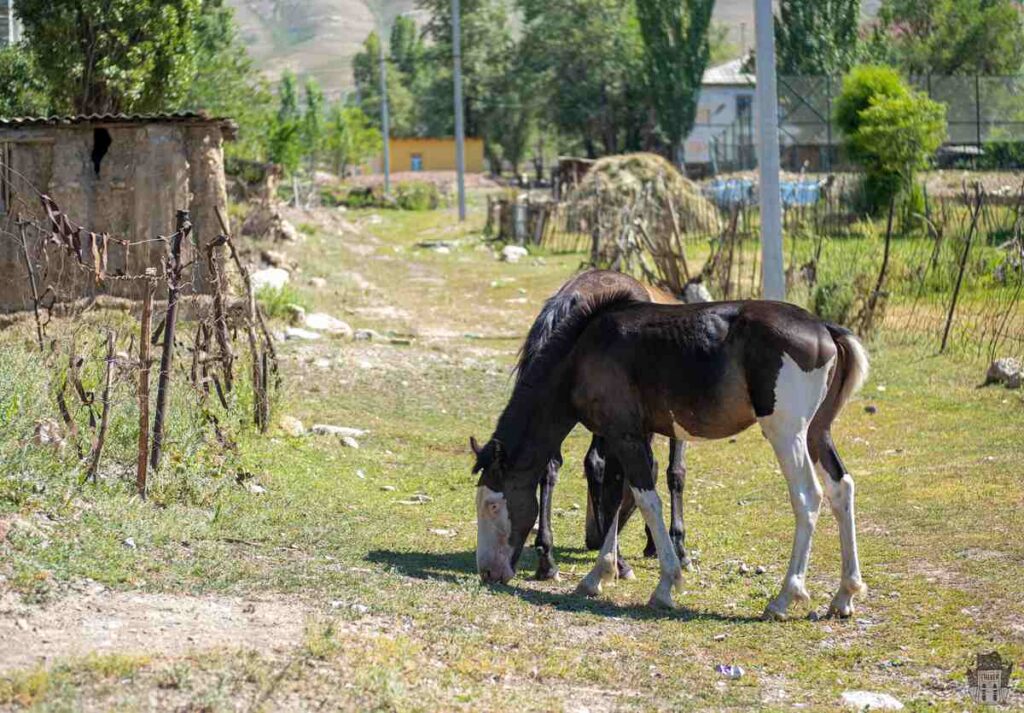

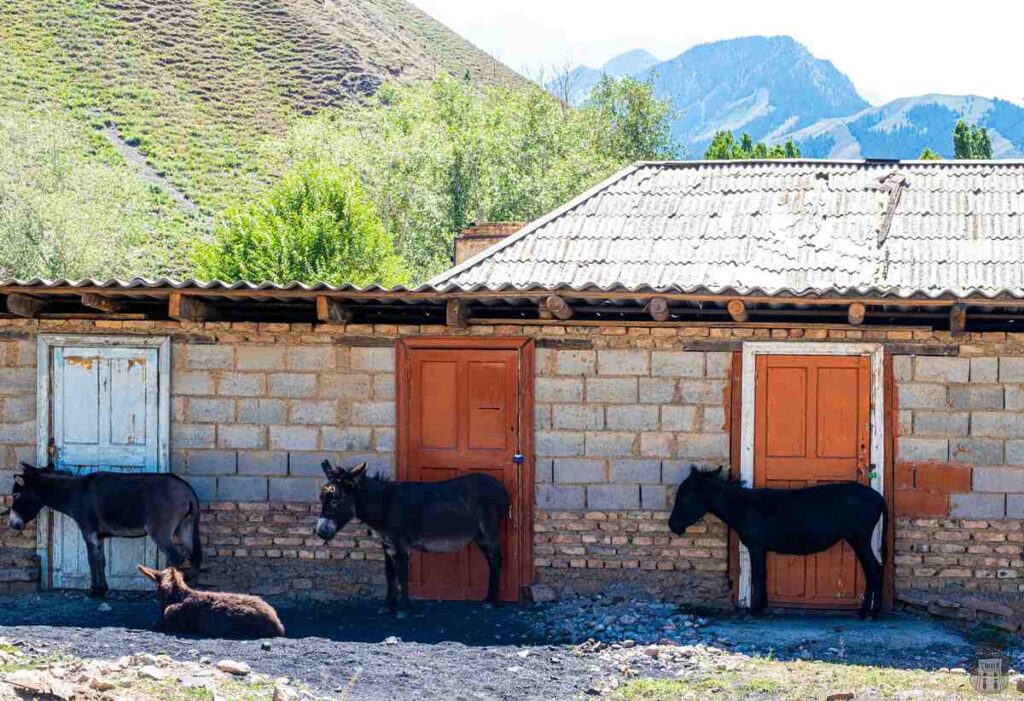

Now the mines are partially converted into makeshift animal shelters, with sections of the surrounding land converted into crops. Buildings from 1955, half-buried and with collapsed roofs, remain as evidence of the village’s industrial heritage, while other structures are still closed and inaccessible. One can see children in the street playing with water from the fountains, women hanging out their laundry and various animals such as horses, sheep and donkeys running free around the town. Inside some houses, residents welcome me for a meal and some kefir. I spend the night as a guest of a family. I ask the head of the family what it is like to live in the winter there: ‘It is becoming more and more challenging, the temperatures sometimes plummet to -40 degrees, making it necessary to use more blankets to keep warm. As you can see, our houses have not been modernised, and the cold infiltrates easily. In addition, the snow often blocks the roads, making travel difficult. The state has abandoned us‘.

Environmental Challenges and the Legacy of Uranium

The remnants of uranium mining and processing have left their mark on the environment in the entire area, which extends beyond the village boundaries. In the Tuyuk- Suu valley there is the largest of four still existing radioactive mounds where cattle can often be found grazing. With heavy rains and landslides, the uranium contamination risks reaching waterways that feed the Syr Darya, a river that runs through the Fergana Valley, the fertile agricultural heart of Central Asia.

According to a 2017 European Union (EU) estimate, Central Asia is grappling with around 1 billion tonnes of toxic uranium waste, buried in seven landfills scattered across the region. Kyrgyzstan hosts three of these sites. After using Central Asia as a source of radioactive materials during the Soviet era, Moscow has left the countries of the region ‘alone with a horrible problem that they are unable to deal with,’ writes Baktygul Stakeyeva, an environmental engineer from MoveGreen, a youth environmental movement.

International efforts, led by organisations such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), have addressed the environmental and health risks posed by these abandoned uranium mines. Despite the challenges, there is a glimmer of hope for the Ming-Kush. The EBRD, the European Commission, Belgium, Norway, Switzerland, the United States, and the IAEA have allocated EUR 85 million for the clean-up of seven uranium sites in Central Asia and EUR 15 million to prepare the necessary landfills. With funding from the Central Asia Environmental Remediation Account (ERA), the project has progressed in Min-Kush and Shekaftar, with work carried out including the sealing of mine shafts, waste transfer and the demolition of industrial facilities. Thanks to these interventions, Ming-Kush, the village of a thousand birds, could regain its clean environment and with it return to flight.

Urbex location: