If the skull is facing the wall, it means that the person has committed sins in life, and therefore will go to hell.

Video

Position

The Catacombs of Paris are an underground ossuary whose official name is “Ossuaire Municipal”. They are located near Place Denfert-Rochereau, in the 14th arrondissement, on 1 Avenue du Colonel Henri Rol-Tanguy.

They can be easily reached by metro with lines 4 and 6, or alternatively by bus 38 and 68.

For any other information, please visit the official website http://catacombes.paris.fr/en.

History

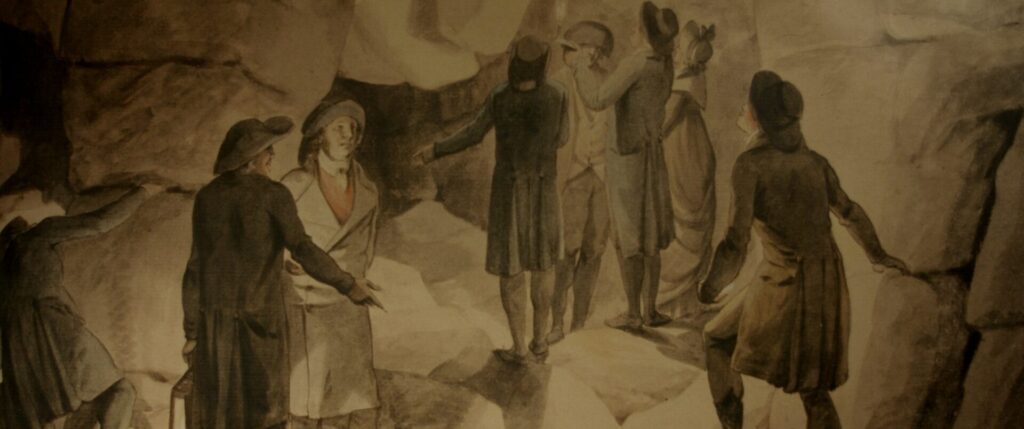

The history of the Catacombs of Paris dates back to the end of the 18th century, when important health problems related to the city’s cemeteries led to the decision to move their contents underground.

The Parisian authorities chose a site that was easy to access and located outside the capital: the old quarries of Tombe-Issoire, below the Montrouge plain. Exploited since at least the 15th century and then abandoned, these quarries form a small part of the labyrinth that extends under the city for about 800 hectares. The development of the site and the organisation of the transfer of the bones are entrusted to Charles-Axel Guillaumot, inspector of the General Inspectorate of the Quarries of Paris, or CIG. This service, set up on 4 April 1777 by Louis XVI, has the task of monitoring and consolidating the quarries abandoned following a series of serious land collapses in Paris in the mid 18th century.

The first evacuations took place between 1785 and 1787 and hit the most important cemetery in Paris, the Santi-Innocenti cemetery, already condemned in 1780 after almost ten centuries of consecutive use. Some cemeteries were located in the middle of the largest Parisian market, where the Les-Halles shopping centre is located today. In those days, because of the smells and smoke from the graves, wine was turned into vinegar and milk became salty. Perfumes of any kind did not work against this acrid smell. It was said that if you were on your way to Paris, you could smell the city before you even saw it.

Given all these problems, they decided to build walls around the cemetery, open graves years old, empty the bones and put the corpses inside. The bones they pulled out of the old graves went to fill the walls. At that time people were not afraid of death, because they were in contact with it constantly.

But it happened that one fine spring day in 1780 a wall in the mortuary collapsed, releasing everything that was contained in the graves into the basement of a house. It was therefore decided to close that cemetery, and others that were kept in similar conditions.

At that point a light bulb was lit. We have to clean our cemeteries, and we have to fill the quarries underground for subsidence problems. We have the solution!

But some criticism arose. In fact, in those days, being so close to hell, crammed underground, and so far from the church and unprotected, could be a problem. “What will our ancestors do when they wake up on Judgment Day?” they wondered.

So they hired priests to go into the quarries to sanctify, and every year a mass was organized for the dead. Nowadays there are no masses anymore, because the catacombs are state property. Christians, on the other hand, decided to write small prayers to put inside the skulls.

Returning to us, six years later, the tombs and mass graves were emptied of their bones, which were then transported at nightfall to avoid hostile reactions from the Parisian population and the Church. The bones are then unloaded through two service shafts in the quarry and then distributed and piled up in the tunnels by the workers. The transfers continued after the Revolution until 1814 with the suppression of parish cemeteries in the centre of Paris such as Saint-Eustache, Saint-Nicolas-des-Champs and the Bernardins convent. They resumed in 1840 during Louis-Philippe’s urban works and during the Haussmannian construction sites from 1859 to 1860. The site was consecrated “Municipal Ossuary of Paris” on 7 April 1786 and from that moment on it appropriated the mythical term “Catacombs”, referring to the catacombs of Rome, an object of public fascination since their discovery.

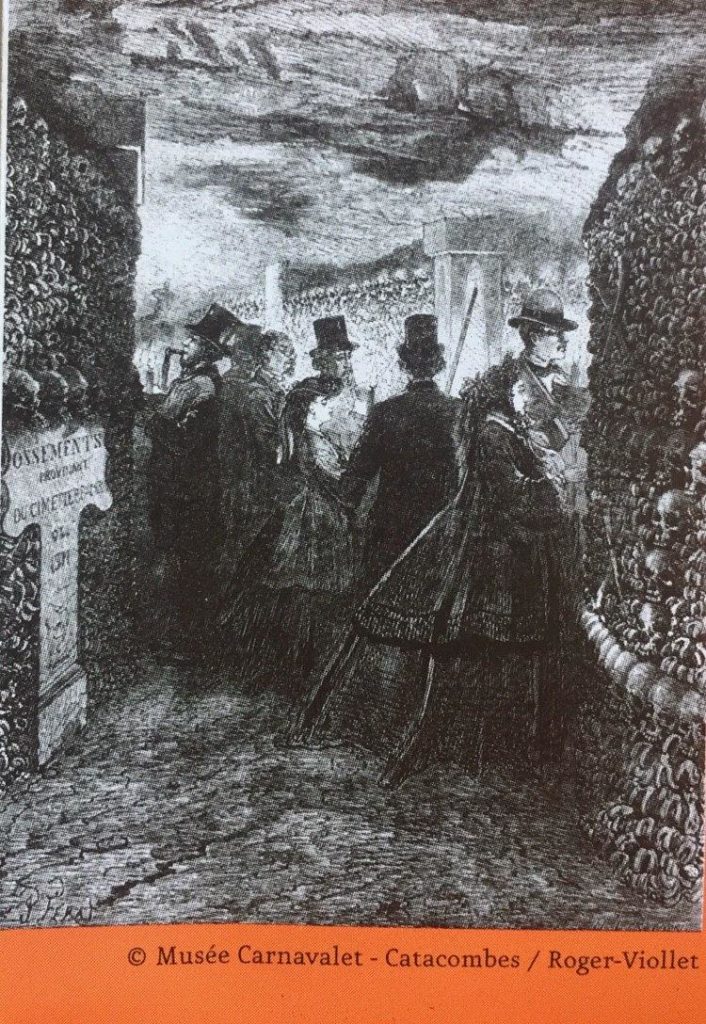

From 1809, the Catacombs became accessible to the public by appointment, and at the end of the tour a register was opened to collect visitors’ impressions.

Over the years, the ossuary has welcomed many famous people: in 1787, the Count of Artois, the future Charles X, visited the ossuary in the company of the ladies of the court; in 1814, the Austrian Emperor Franz I visited them in turn and, in 1860, Napoleon III descended with his son.

During the course of the 19th century, the way in which they were visited changed constantly, from total closures to monthly or quarterly openings. Today the Catacombs of Paris are accessible to everyone without authorisation and receive almost 550,000 visitors a year.

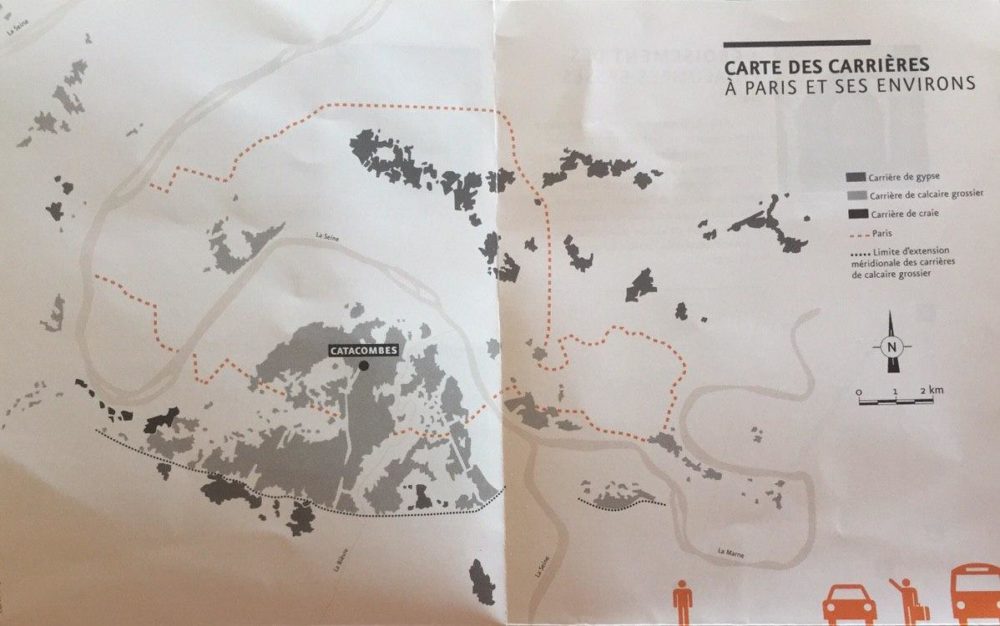

Geology and quarries

Between the street level and the catacombs are layers of rock about 45 million years old.

In this geological era, Paris and its surroundings were covered by a tropical sea. Several meters of sediment and mud accumulated on its seabed, which over time became limestone. The level of the Catacombs corresponds to this limestone bank which represents the period called “Lutetian”, referring to the name of Paris in Roman times, Lutetia. Dated between 48 and 40 million years ago on the geological scale, this bank is divided into upper luteum, middle luteum and lower luteum. The quarries occupy the upper and middle level, while within the course of the ossuary, a water well known as the “quarrymen’s footbath” descends to the lower level.

A great variety of sediments is present in Paris, providing since ancient times important quantities of building materials, from sand, sandstone, clay and chalk. However, it is precisely Lutetian limestone, known as “pierre de Paris”, which provided most of the building stone until the beginning of the 20th century.

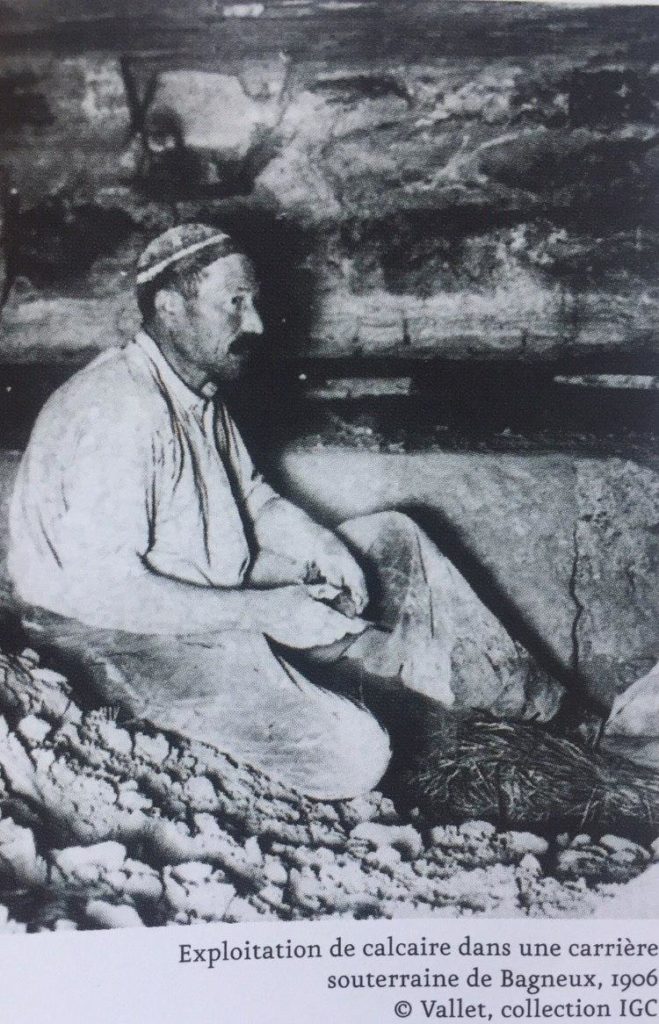

The old quarries, which have become too deep, are gradually evolving towards underground mining with the excavation of tunnels that reach the benches lower down into the rock. Turned pillars were left in place to support the ground and, in the 15th century, a system of shafts facilitated the raising of the stone.

The method of mining with harpooning and tamping was developed in the late Middle Ages. It consists of extracting all the stone from the quarry without leaving any supporting parts, and then consolidating it with the construction of pillars called “hand pillars”. Among these, stone walls called “alloys” are mounted to contain the cut filling material and facilitate circulation in the quarry. Unfortunately the excavation of these tunnels was little regulated by the Parisian authorities; the quarries in Paris were definitively condemned by the decree of 15th September 1776, following numerous collapses in the heart of the city.

The ossuary

The municipal ossuary of the Catacombs is one of the largest ossuaries in the world.

Before it opened to the public in 1809, it underwent a significant decorative development under the aegis of Inspector Héricart de Thury, who transformed the site according to his museographic and monumental vision.

You enter the ossuary through a metal door framed by two pillars decorated with white geometric motifs on a black background, on whose architrave is engraved this gloomy warning: ‘Stop! This is the empire of death: ‘This Alexandrian is taken from the translation of Jacques Delille’s Aeneid (hymn VI). It is the phrase with which Aeneas is greeted by Charon, the ferryman who allows to cross the river Styx to reach the underworld. On the left wall of the first room, a plaque commemorates the creation of the ossuary.

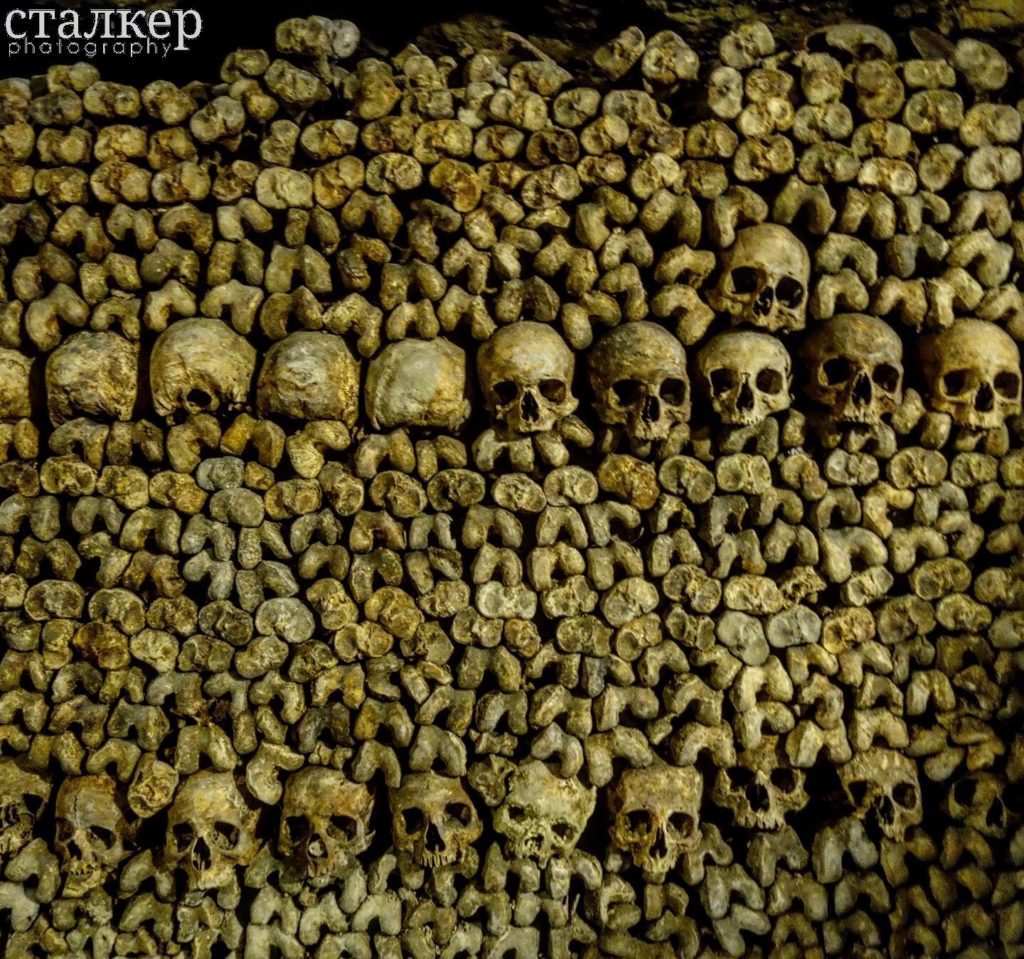

Six million French bones lie in about 780 kilometres of winding galleries, mostly inaccessible to the public, at an average height of one and a half metres. Their total surface area is 10,933 m2. On each side of the visit route, the bones form long alignments of femoral or tibial heads on the same model as the haggons of the quarrymen, of which only the apophyses can be seen. Behind the facets accumulate the remaining bones, often very fragmented by the consequences of their fall.

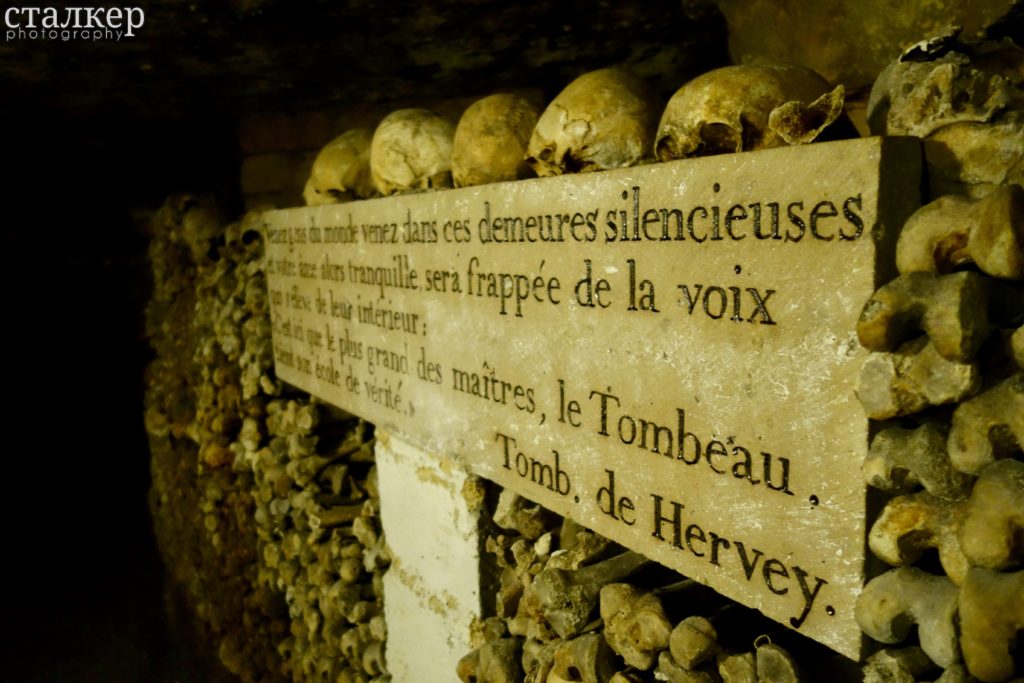

The friezes made of skulls are arranged at several heights and slightly protruding from these bone walls, which show a decorative research of a romantic-macabrian type. However, behind these alignments, thousands of skeletons remain mixed in disorder. The engraved plates indicate the origin and the year of the transfer in front of the bones; others often bear grandiloquent quotations of great authors, or of other celebrities of the early nineteenth century, in French or Latin.

Along the route there are also masonry monuments in ancient and Egyptian style in the form of Doric pillars, altars, skulls or tombs. Names inspired by religious or romantic literature and Antiquity are attributed to certain places: the tear sarcophagus, the Samaritan fountain or the burial lamp.

At the centre of a gallery that widens into a rotunda, the Samaritaine fountain was built in 1810 to collect water from the aquifer, discovered by the workers during the work of the ossuary. It refers to the episode of Christ and the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well, evoked by the inscription: “Whoever drinks this water will still be thirsty”. But whoever drinks the water I give him will not thirst for eternity…”. It was also called the “fountain of Lethe” or “of oblivion”, by analogy with the river of Greek mythology, where the souls of the dead quenched their thirst to forget the circumstances of their existence.

Further on, a larger hall or chapel, known as the “crypt of the sacellum”, has an altar, where the Office of the Dead was celebrated for a long time. The altar, a reproduction of an ancient tomb discovered in 1807 on the banks of the Rhone between Vienne and Valence, is actually a masked consolidation, made necessary by a landslide in 1810. The monument bears an engraving: “Asleep from death, here are our ancestors. “The room also has a large white cross and small stone stools.

After a bend in the gallery, a stone column rises in a recess, surmounted by an ancient shaped basin, called the “sepulchral lamp”. This monument, the first to be built in the ossuary, was used to burn pitch resin, as the air was contaminated with strong, acrid odours, making it difficult for the workers in charge of the transfers to breathe. Maintenance of a firebox was in fact the best way to ensure ventilation during underground work. It was used to supervise the dead and, more prosaically, to improve air circulation before the ventilation shafts were built.

In another room is the “tomb of Gilbert” or the “tear sarcophagus”, which is actually a simple consolidation. It is dedicated to Nicolas Gilbert (1750-1780), a cursed poet whose verses are engraved on the monument. It was the engineer of the Caly Mines who had the unusual idea of building this false tomb amid thousands of bones with no burial place. The following tunnels contain the remains of the victims of the fighting in the Tuileries and the Revolution.

Further on is the only tombstone contained in the ossuary: that of Françoise Gellain (or dame Legros) whose tombstone was transferred from the Vaugirard cemetery, which was emptied in 1860. This woman fell in love – without ever having seen him – with a prisoner from the prison of Bicêtre, the adventurer Latude (1725-1805), of whom she had found a note thrown from a window. He then dedicated his life to freeing him. When he reached his goal, he received the Prix de Virtue from the Académie Française in 1784.

Near the exit of the ossuary, a large room entirely surrounded by bones, called “Crypt of the Passion” or “Round of Shin”, is formed by a strange sculpture of bones in the shape of a barrel. It consists exclusively of shins, around a consolidation pillar. It was in this room that the clandestine concert of April 2, 1897 took place.

Anxious to bring an educational dimension to the route, Héricart de Thury had cabinets built, one dedicated to mineralogy, the other to pathology. The latter showed samples referring to diseases and bone deformations according to the research of Dr. Michel-Augustin Thouret in 1789. The last educational tool is the set of plaques decorated with religious and poetic texts distributed in the galleries, aimed at taking the visitor into a state of introspection and reflection on death.

The Catacombs of Paris have been the subject of several studies on the underground environment. Shortly after their opening, two researchers from the National Museum of Natural History became particularly interested in this world: Jacques Maheu, a botanist, a scholar of flora in lightless environments, and Armand Viré, a speleologist and naturalist, who highlighted the existence of some cave-dwelling crustaceans. Héricart de Thury also carried out an experiment in 1813: he introduced four golden carp into the basin of the Samaritaine fountain; the fish survived, but did not reproduce and ended up going blind.

In 1861 it was Félix Tournachon, better known as Nadar, who experimented with artificial light for three months. As darkness made the exposure time very long, the photographer used mannequins to portray workers in the workplace.

Today, research into pathologies continues during the ossuary consolidation campaigns. The preventive preservation of the bones in a very humid underground environment, the respect for human remains and the enhancement of the geological, archaeological and historical heritage are a real challenge for the Paris Catacombs.

With a change of meaning, the term “Catacombs of Paris” – a proper name given to the section of the quarry transformed into an ossuary in the 18th century – is now used by extension and by mistake to refer to quarries extending under Paris and sometimes beyond Paris.

Details and additional information

– The museum covers an area of 2 km, when the catacombs in all their size extend 280 km below the French capital.

– The catacombs have a constant temperature of 14°.

– The length of the tunnels in the ossuary is 800 metres.

– The average time of a tour is 45 minutes

– You will have to take a total of 213 steps (130 down, and 83 more to reach the exit).

– The depth of the catacombs can range from 1 to 21 meters.

Curiosities

The catacombs contain the bones of over six million Parisians, including many celebrities from French history buried in Paris. But their remains have joined those of millions of anonymous Parisians, none of whom have yet been identified.

Charles-Axel Guillaumot, the first inspector general of the quarries and responsible for the consolidation and transfer of the bones, was buried in 1807 in the cemetery of Sainte-Catherine, whose contents were then transferred to the catacombs. Several famous figures in French history found their last resting place in the ossuary: Nicolas Fouquet, superintendent of finance of Louis XIV, buried in the convent of Filles-de-la-Visitation-Sainte-Marie, transferred in 1793; Minister Colbert, buried in a vault of the church of Saint-Eustache, violated during the Revolution and transferred to the Catacombs.

From the church of Saint-Paul come the remains of Rabelais, François Mansart, Jules Hardouin-Mansart, the man in the iron mask and Jean-Baptiste Lully. From Saint-Étienne-du-Mont are transferred those of Racine, Blaise Pascal and Marat, Saint-Sulpice and Montesquieu; from the cemetery of Saint-Benoît, those of the engravers Guillaume Chasteau and Laurent Cars, Charles and Claude Perrault, and Héricart de Thury, uncle of Louis-Étienne, inspector of the quarries. From the cemetery of Ville-l’Évêque come the bodies of the 1,000 Swiss guards massacred at the Tuileries in 1792 and the 1,343 guillotined at the Carrousel or Place de la Concorde between 1792 and 1794, including Charlotte Corday. With the transfer of the bones from the cemetery of Errancis under the Restoration, Danton, Camille Desmoulins, Lavoisier and Robespierre also joined the catacombs.

The martyr Saint Ovid, buried in the catacombs of Rome, was brought back to Paris by Pope Alexander VII. His remains were placed in the Capuchin convent, and later the bones were transferred to the ossuary on March 29, 1804. He is therefore the only one who was buried in two catacombs at the same time. The acroterial tomb of Philibert Aspairt and the discovery of his body in 1804 would only be a hoax by the Mining Inspector.

The streets of Paris

The long, narrow corridors follow the layout of the surface streets. In fact, some street names that you will find engraved in some stone plaques in the subsoil were to represent exactly those of the surface. Nowadays the plan of Paris has changed, and only a few streets remain with their original names.

Underground signage

The architects and engineers of the general inspection of the quarry signed their work by engraving in stone the site number, their initials and the year. Thanks to these inscriptions it is possible to follow the consolidation and improvements made at the end of the 18th century. Thus “85 G. 1878” indicates the 85th intervention/wall made by Charles- Axel Guillaumot in 1878.

Archives and ancestors

Thanks to some archives in Paris, it is possible to retrace the burial place of your possible ancestors. All this thanks to King Francis I, who in 1500 decided to keep a register where every marriage, birth and death had to be recorded, with the obvious exception of Protestants.

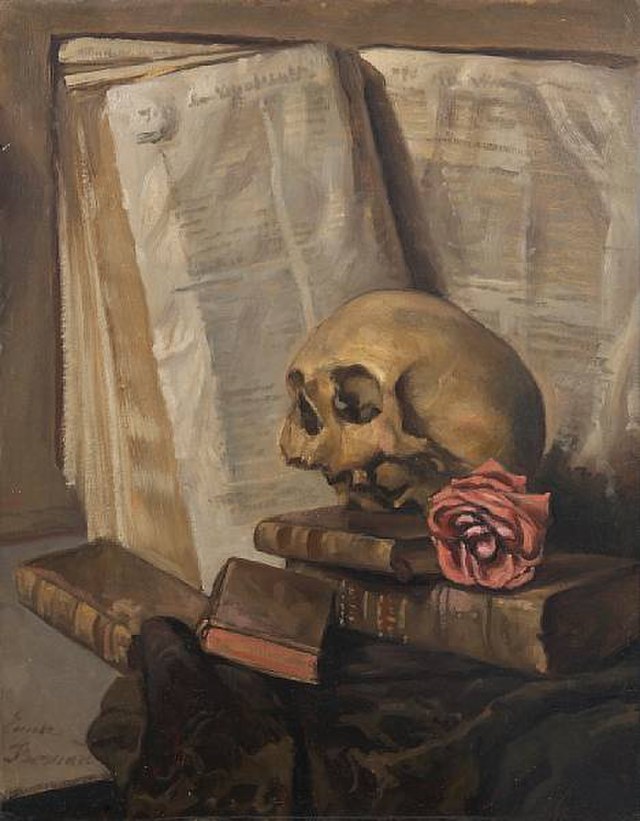

Memento Mori

The catacombs of Paris were built during the Memento Mori movement (remember that you must die, an artistic or symbolic reminder of the inevitability of death). In fact you will find many signs and poems that remind you of how you must enjoy your life as temporary and ephemeral. But, everything will depend on the choices that the subject has made in life. That said, to emphasize this message, the skulls that are facing the wall will go to hell. The skulls that are facing the viewer will go to heaven. Obviously the workers did not know who was going to hell, and who was going to heaven, so they placed them randomly. Proof of this can be found in whole piles of some nuns’ skulls facing the wall.

Identify the sex of a skull

There are a number of features of the skull that are more commonly found in males than females and these are the indicators used by forensic archaeologists to determine the sex of an individual.

Generally, male skulls are heavier, the bone is thicker and the areas of muscle attachment are more defined than females. There are also key differences in the appearance of the forehead, eyes and jaw between men and women that are used to determine the sex of a skull.

Forehead and brow ridge:

When viewed in profile, female skulls have a rounded forehead (frontal bone). Male frontal bones are less rounded and tilted backwards at a gentler angle. This ridge along the forehead is prominent in males and much smoother in females. Since this ridge is located above the eyes (orbits), this structure is known as the supraorbital ridge.

Ocular cavity:

Females tend to have round eye sockets with sharp edges at the upper edges. In contrast, male skulls have much more square orbits with smoother upper edges of the eyes.

Jawbone :

The males have square jaw and the line between the outer edge of the jaw and the ear is vertical. In the females, on the contrary, the jaw is much more pointed and the edge of the jaw descends gently towards the ear.

The problem comes when some women have similar characteristics to those of men, and vice versa. Also for the children we cannot understand if they are male or female, as they have not yet reached puberty and some bones have not yet closed.

French revolution

In the heart of the ossuary, the plaques evoke significant events of the French Revolution: the “fight in the Réveillon factory in Faubourg Saint-Antoine on 28 April 1789”, where the workers’ demonstration ended in a massacre, and the “fight at the Château des Tuileries on 10 August 1792” which pitted the Swiss guards against the insurgents of the Parisian sections. At that time, the ossuary was temporarily used as a mortuary where the bodies of the people killed in the clashes were placed.

During the French Revolution it was decided to change the Gregorian calendar, as it was too “Christian”, and to have its own. So if you ever find a 40r, instead of any date, it will mean the 40th Republican year after the revolution, i.e. 1829.

The revolution leaves behind any memories related to the king and the church, so even the streets change name, and even the three petals related to the monarchy are deleted.

Crypt of passion: The Barrel

At the centre of this space called “crypt of passion” or “shin rotunda” there is a supporting pillar masked by a covering of skulls and shins in the shape of a barrel. On April 2, 1897, a night concert was held here between midnight and two in the morning. Forwarded by the press, it would have welcomed more than a hundred participants, who came to hear, among other things, Chopin’s funeral march and Camille Saint-Saens’ macabre Danse. Already at this moment, the place fascinated Parisians in search of excitement.

Movies

The catacombs of Paris have also been the scene of horror films, with protagonists and events through fantasy stories such as:

– Pierre Tchernia’s Gaspar

– Catacombs of David Elliot and Tomm Coker

– Paris by Cédric Klapisch

– Catacombes (As Above, so Below) by John Erick Dowdle

Warnings

No one who suffers from respiratory or heart disease, sensitive people and children are not allowed in.

Care must be taken when walking to keep a certain distance from the walls, and to move your backpacks in front of you. There have been cases where entire walls of bones have collapsed due to the negligence of visitors.

You can be legally prosecuted (even with years in prison) if you ever plunder the catacombs of some finds.

Description

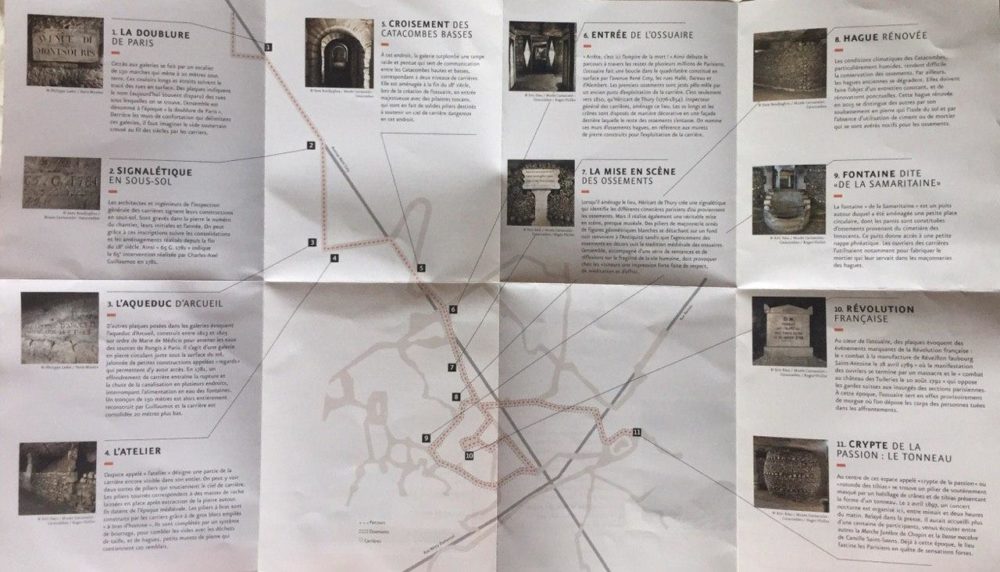

The tour of the Catacombs begins at 1, avenue du Colonel-Henri-Rol-Tanguy. After the small ticket office, a staircase of one hundred and thirty steps gives access, twenty meters down, to small rooms with explanatory panels on the history of the Catacombs and temporary exhibitions.

A gallery exits to the south, under René-Coty Avenue, formerly Avenue du Parc-de-Montsouris. Further on, the route follows the narrow consolidation galleries of the Arcueil aqueduct, built for Marie de Médicis, which supplied water to the Palais du Luxembourg. The aqueduct is supported by a massive masonry structure, bounded by two side tunnels, connected from side to side by several transverse tunnels. Today, for obvious reasons, it is dry.

Later I reach the Atelier, the former Lutetian limestone quarries, which are rough-looking and equipped with numerous departures from galleries closed by gates. It is one of the rare sectors of the underground quarries that has retained its appearance at the end of the exploitation. The ceiling of the quarry is supported by turned pillars (in stone) or by arm pillars (in overlapping stones, moved with the mere force of the arms) and the walls are in “haggis” which hold the blocks in place. The smaller bones have been positioned at the back, while the larger bones such as femurs and skulls have been positioned at the front, and stand “standing” only between them. The spaces between the stones were filled with smaller ones, and in this case with human bones. A gently sloping corridor allows access to the lower levels.

The visitor then enters the Port-Mahon gallery. These sculptures made of stone from 1777 to 1782 are the work of a quarryman named Décure, known as Beauséjour, a veteran of Louis XV’s armies. According to Le Conducteur portatif of 1829, he was a soldier enlisted in 1756 in Richelieu’s army during the reconquest of Menorca. After being discharged, he joined the Quarry Inspectorate to supplement his modest salary. Working during the day on consolidation work under the direction of Guillaumot, he sculpted a model after his work and painted various views of the fort of Port-Mahon, the main town on the island of Menorca, in the Balearic Islands, where he would be held prisoner by the British for a time. Wanting to perfect his work, he began to create a staircase from the upper level of the quarry, but this caused a collapse that killed him. We can say that Décure was the first cataphile to be named.

Not far away we find the footbath of the quarrymen, a small well that contains a particularly clear mass of water, once used by the workers who worked on the consolidation of the ossuary. Equipped with a railing, it owes its name to the transparency of the water, which makes it barely visible to the uninformed visitor who wet his feet when going down the last immersed steps of the access staircase. This was the first geological well dug underneath Paris, whose orythrognostic section was raised in 1814 by Héricart de Thury. Its aim was the recognition of the geological constitution of the subsoil. The tunnel then gained height in the passage known as the “double quarry”. The visitor then reaches the ossuary, whose vestibule is also used for temporary exhibitions.

On the map:

Source:

- https://www.futurelearn.com/courses/forensic-facial-reconstruction/0/steps/25656

- http://catacombes.paris.fr/